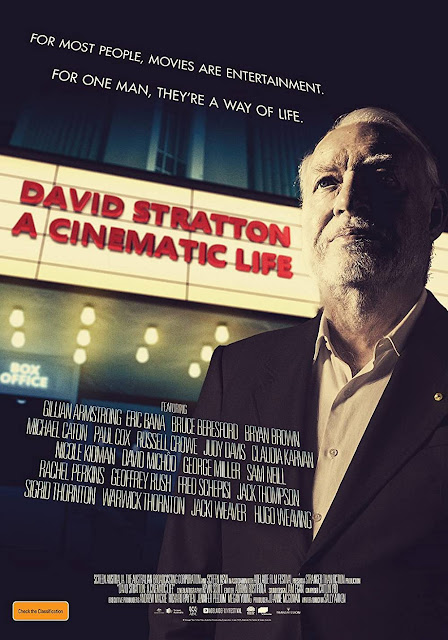

Even in the world of Internet criticism and the democratisation of opinions about media, there is still one name and one name

only who is the most important film critic in Australian history: David

Stratton. The Oceanic answer to Roger Ebert, gaining mainstream attention

through the Australian version of At The Movies with fellow critic Margaret

Pomeranz, he basically embodies everything I both love and hate about the

typical newspaper film critic. He has a very evident love for the medium and

helped build up the Sydney Film Festival, but he also employs a lot of the

faux-profundities and literary snootiness that I have railed on many times

before. Still, regardless of all that, I find myself almost required to show

respect where it’s due because of his importance to the industry. Have to

admit, I wasn’t exactly anxious to check this film out, given how this is the

sort of critic I usually try to avoid out in the wild, but considering how this

year has been for Aussie cinema already, I reckon it’s worth being given its

time in the sun on this blog.

The plot (such as it is): David Stratton reflects on his own

life as it connects to films, both with my lifelong fascination with the

artform and how he relates to it

personally. While numerous prominent Australian actors and filmmakers talk

about Stratton and his impact on the Australian film industry, we see said film

industry through some of its most important contributions to world cinema.

Even though this is touted and framed as a look into the

life and times of David Stratton, this is as much a look into the history of

Australian cinema itself as it is a look at Stratton. From iconic favourites

like Muriel’s Wedding and The Castle to international classics like Strictly

Ballroom and the Mad Max series to underplayed gems like Wake In Fright and

Evil Angels (the latter of which is underplayed due to historical dilution

involving the phrase “The dingo stole my baby”), a very wide net is cast in

regards to Aussie cinema. Hell, it even goes all the way back to the earliest

days of the medium with The Story Of The Kelly Gang, a 1908 lost film that is

regarded as the first feature-length film ever produced.

Between all this and

the anecdotes provided by the interviewees, we get a pretty vivid look at the

timeline of Aussie film culture, serving as a primer for a large number of

cultural and aesthetic milestones. Even as a native, it is quite fascinating to

look at the colourful and commendable history of this little island that is

largely used as a joke about wildlife and beer so shite that we exported it to

idiots who would actually drink it.

So, how does this relate to Stratton? I mean, his name is in

the title and it’s purportedly about his life, so where does Aussie film

history fit into it? Well, for Stratton, film is his life. The snapshots of his life that we get, from his

strained relationship with his family to his feelings of isolation when first

arriving in Australia, are depicted in relation to similar scenes in Aussie

films. That, and a few tidbits from interviewees, but for the most part, we are

seeing a man who relates to the world, and his adopted home, through the medium

of cinema. When we see his extensive filing system for the films he’s watched

(over 20,000 of them) and his written thoughts on each, even those unfamiliar

with his work will see a man who is truly dedicated to his love for cinema. Of

course, the film doesn’t exactly deify him either as they freely admit that he

is still a man wielding only a singular opinion, outlined through his encounter

with Romper Stomper director Geoffrey Wright and his changing perspective on

The Castle.

Of course, when I

see his filing system, I see something a bit different. It’s an incredible

irony that, in watching a film about a man who connects his own life to films,

I would see a film that I can connect to my own life. The obsessing over and

encyclopaedic knowledge of what he’s seen, getting a job as an usher at the

Sydney Film Festival so he could watch free movies, feeling that he is doing a

service to not only his home of Australia but also to cinema at large by

discussing and promoting films as he does; I can’t be the only cinephile who

can see shades of their own history in those actions. Hell, even down to a moment

about his grandmother taking him to see a lot of movies when he was a kid, a

moment I watched in the cinema while sitting next to my grandmother.

Now, all of this probably means nothing to those of

you who just want to know what films are worth watching based on my writings.

But that’s the thing: Emotional and personal connections to films, no matter

how subjective, have merit. Films serve a great many purposes for the average

person, and among them are as a reflection of one’s own world in a way that can

be easily digested through the veneer of being acted out on screen. And with this film, I found kinship with a man

who I honestly didn’t have too high an opinion of in the first place because,

quite frankly, he has much the same approach to cinema as I do; as I’m sure

many others do as well.

All in all… wow. In no uncertain terms, this is a film that

simultaneously made me proud to be an Australian, a film critic and an

Australian film critic. As much about the history of one of Australian cinema’s

most important figures as it is a look into Australian cinema itself, this is

an amazingly-paced, edited and endlessly engaging documentary. Quite honestly,

I can see myself watching this many times over and it’s quite rare that I ever

say that about a film, even some of my all-time favourites. As much as I hold

Silence in rather high regard for its relevancy and poignancy, this film still

manages to strike a stronger chord with me personally. Kind of fitting, given

this is a film all about personal connections with films.

No comments:

Post a Comment